Both adult and youth leaders approve advancement in Scouts BSA. This permits greater emphasis on standards and more consistency in measurement, but it also places another level of importance on teaching and testing. As Scouts work with one another, learning takes place on both sides of the equation as they play teacher and student in turn. Parents or guardians are involved at home encouraging, mentoring, and supporting, but they do not sign for rank advancement requirements unless they serve as registered leaders and have been designated by the unit leader to approve advancement or are Lone Scout friends and counselors (see “Lone Scouting,” 5.0.3.0).

Throughout this publication the term “Scout” generically refers to any youth member of a troop or a Lone Scout, regardless of rank. The phrase “Scout rank” refers to the first rank every Scout earns.

Advancement at this level presents a Scout with a series of challenges in a fun and educational manner. As the youth completes the requirements, the aims of Scouting are being achieved: to develop character, to train in the responsibilities of participating citizenship, to develop leadership skills, and to develop physical and mental fitness. It is important to remember that in the end, badges recognize that Scouts have gone through experiences of learning things they did not previously know. Through increased confidence, Scouts discover or realize they are able to learn a variety of skills and disciplines. Advancement is thus about what Scouts are now able to learn and to do, and how they have grown. Retention of skills and knowledge is then developed later by using what has been learned through the natural course of unit programming; for example, instructing others and using skills in games and on outings.

Advancement, thus, is not so much a reward for what has been done. It is, instead, more about the journey: As a Scout advances, the Scout is measured, grows in confidence and self-reliance, and builds upon skills and abilities learned.

The badge signifies that a young person—through participation in a series of educational activities—has provided service to others, practiced personal responsibility, and set the examples critical to the development of leadership; all the while working to live by the Scout Oath and Scout Law.

The badge signifies a young person has provided service to others, practiced personal responsibility, and set the examples critical to the development of leadership.

4.2.0.1 Scouting Ranks and Advancement Age Requirements

All Scouts BSA awards, merit badges, badges of rank, and Eagle Palms are only for registered Scouts, including Lone Scouts, and also for qualified Venturers or Sea Scouts who are not yet 18 years old. Venturers and Sea Scouts qualify by achieving First Class rank as a Scout or Lone Scout, or Varsity Scout (prior to January 1, 2018). The only exceptions for those older than age 18 are related to Scouts registered beyond the age of eligibility (“Registering Qualified Members Beyond Age of Eligibility,” 10.1.0.0) and those who have been granted time extensions to complete the Eagle Scout rank (“Time Extensions,” 9.0.4.0).

There are seven ranks in Scouts BSA that are to be earned sequentially no matter what age a youth joins the program.

The Scout rank is oriented toward learning the basic information every youth needs to know to be a good Scout. It starts with the Scout demonstrating knowledge and understanding of the Scout Oath, Scout Law, Scout motto, and Scout slogan and then introduces the Scout to basic troop operations and safety concerns.

Tenderfoot, Second Class, and First Class ranks are oriented toward learning and practicing skills that will help Scouts develop confidence and fitness, challenge their thought processes, introduce them to their responsibilities as citizens, and prepare them for exciting and successful Scouting experiences. Requirements for the Scout, Tenderfoot, Second Class, and First Class ranks may be worked on simultaneously; however, these ranks must be earned in sequence. For information on boards of review for these ranks, see “Particulars for Tenderfoot Through Life Ranks” 8.0.2.0, especially point No. 7.

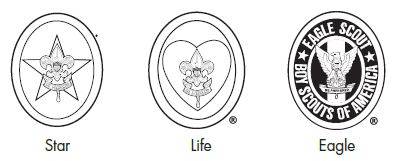

All requirements for Star, Life, and Eagle, except for those related to merit badges, must be fulfilled after the successful completion of a board of review for the previous rank.

In Scouts BSA, advancement requirements must be passed as written. If, for example, a requirement uses words like “show,” “demonstrate,” or “discuss,” then that is what Scouts must do. Filling out a worksheet, for example, would not suffice.

4.2.1.0 Four Steps in Advancement

A Scout advances from the Scout rank to the Eagle rank by doing things with a patrol and troop, with adult and youth leaders, and independently. A well-rounded and active unit program that generates advancement as a natural outcome should enable Scouts to achieve First Class in their first 12 to 18 months of membership. Advancement is a straightforward matter when the four steps or stages outlined below are observed and integrated into troop programming. The same steps apply to members who are qualified to continue with Scouts BSA advancement in Venturing or Sea Scouts. In these cases, references to troops and various troop leaders would point to crews and ships, and their respective leaders.

4.2.1.1 The Scout Learns

With learning, a Scout grows in the ability to contribute to the patrol and troop. As Scouts develop knowledge and skills, they are asked to teach others and, in this way, they learn and develop leadership.

4.2.1.2 The Scout Is Tested

The unit leader authorizes those who may test and pass the Scout on rank requirements. They might include the patrol leader, the senior patrol leader, the unit leader, an assistant unit leader, or another Scout. Merit badge counselors teach and test Scouts on requirements for merit badges.

Once a Scout has been tested and signed off by someone approved to do so, the requirement has been met. The unit leader is accountable for ensuring proper advancement procedures are followed. A part of this responsibility includes the careful selection and training of those who approve advancement. If a unit leader believes a Scout has not learned the subject matter for a requirement that has been signed off, he or she should see that opportunities are made available for the Scout to practice or teach the requirement. Thus the Scout may complete their learning and further develop the related skills.

4.2.1.3 The Scout Is Reviewed

After completing all the requirements for a rank, except Scout rank, a Scout meets with a board of review. For Tenderfoot, Second Class, First Class, Star, and Life ranks, members of the unit committee conduct it. See “Particulars for Tenderfoot Through Life Ranks,” 8.0.2.0. The Eagle Scout board of review is held in accordance with National Council and local council procedures.

4.2.1.4 The Scout Is Recognized

When a Scout has earned the Scout rank or when a board of review has approved advancement, the Scout deserves recognition as soon as possible. This should be done at a ceremony at the next unit meeting. The achievement may be recognized again later, such as during a formal court of honor.

4.2.1.5 After the Scout Is Tested and Recognized

After the Scout is tested and recognized, a well-organized unit program will help the Scout practice newly learned skills in different settings and methods: at unit meetings, through various activities and outings, by teaching other Scouts, while enjoying games and leading projects, and so forth. These activities reinforce the learning, show how Scout skills and knowledge are applied, and build confidence. Repetition is the key; this is how retention is achieved. The Scout fulfills a requirement and then is placed in a situation to put the skills to work. Scouts who have forgotten any skills or information might seek out a friend, leader, or other resource to help refresh their memory. In so doing, these Scouts will continue to grow.

4.2.2.0 Reserved

4.2.3.0 Rank Requirements Overview

When people are asked what they did in Scouting, or what it is they think Scouts do or learn, they most often mention the outdoor activities, such as camping and hiking. A First Class Scout would surely add first aid or fire building or swimming or cooking or knot tying. And those who made at least Star or Life would doubtless talk about the merit badges they had earned to achieve those ranks—especially those required for Eagle. But these hands-on experiences, as memorable as they are, make up only a portion of what must be done to advance. And the remaining requirements—those beyond the merit badges and skills activities—are generally the most difficult to administer and judge. This section concentrates on those. Consult Volume 1 of the Troop Leader Guidebook for guidance on implementing the others.

The concepts of “reasonable” and “within reason” will help unit leadership and boards of review gauge the fairness of expectations for considering whether a Scout is “active” or has fulfilled positions of responsibility. A unit is allowed, of course, to establish expectations acceptable to its chartered organization and unit committee. But for advancement purposes, Scouts must not be held to those which are so demanding as to be impractical for today’s youth (and families) to achieve.

Ultimately, a board of review shall decide what is reasonable and what is not. In doing so, the board members must use common sense and must take into account that youth should be allowed to balance their lives with positive activities outside of Scouting.

Since we are preparing young people to make a positive difference in our American society, we determine a member is “active” when the member’s level of activity in Scouting, whether high or minimal, has had a sufficiently positive influence toward this end.

4.2.3.1 Active Participation

The purpose of Star, Life, and Eagle Scout requirements calling for Scouts to be active for a period of months involves impact. Since we are preparing young people to make a positive difference in our American society, we determine a member is “active” when the member’s level of activity in Scouting, whether high or minimal, has had a sufficiently positive influence toward this end.

Scouting is a year-round program administered by the adult leaders. Units should not be taking time off during the summer or at other times of the year. Regardless of a unit’s expectations or policy, if a unit takes time off it must count that time toward the Scout’s active participation requirement. The Scout must not be penalized because the unit has chosen not to meet or conduct other activities for a period of time.

Use the following three sequential tests to determine whether the requirement has been met. The first and second are required, along with either the third or its alternative.

- The Scout is registered. The youth is registered in the unit for at least the time period indicated in the requirement. It should also be indicated by the youth in some way, through word or action, that the youth considers himself or herself a member. If a youth was supposed to have been registered, but for whatever reason was not, discuss with the local council registrar the possibility of back-registering the youth.

- The Scout is in good standing. A Scout is considered in “good standing” with a unit as long as the Scout has not been dismissed for disciplinary reasons. The Scout must also be in good standing with the local council and the Boy Scouts of America. (In the rare case the Scout is not in good standing, communications will have been delivered.)

- The Scout meets the unit’s reasonable expectations; or, if not, a lesser level of activity is explained. If, for the time period required, a Scout or qualifying Venturer or Sea Scout meets those aspects of the unit’s pre-established expectations that refer to a level of activity, then Scout is considered active and the requirement is met. Time counted as “active” need not be consecutive. Scouts may piece together any times they have been active and still qualify. If a Scout does not meet the unit’s reasonable expectations, the alternative that follows must be offered.

Units are free to establish additional expectations on uniforming, supplies for outings, payment of dues, parental involvement, etc., but these and any other standards extraneous to a level of activity shall not be considered in evaluating this requirement.

Alternative to the third test if expectations are not met:

If a Scout has fallen below the unit’s activity-oriented expectations, then the reason must be due to other positive endeavors—in or out of Scouting—or due to noteworthy circumstances that have prevented a higher level of participation.

A Scout in this case is still considered “active” if a board of review can agree that Scouting values have already taken hold and have been exhibited. This might be evidenced, for example, in how the Scout lives life and relates to others in the community, at school, in religious life, or in Scouting. It is also acceptable to consider and “count” positive activities outside Scouting when they, too, contribute to the Scout’s character, citizenship, leadership, or mental and physical fitness. Remember: It is not so much about what a Scout has done. It is about what the Scout is able to do and how the Scout has grown.

Additional Guidelines on the Three Tests. There may be, of course, registered youth who appear to have little or no activity. Maybe they are out of the country on an exchange program, or away at school. Or maybe we just haven’t seen them and wonder if they’ve quit. To pass the first test above, a Scout must be registered. But it should also be made clear through the Scout’s participation or the Scout communicating in some way that he or she still considers himself or herself a member, even though—for now—the unit’s participation expectations may not have been fulfilled. A conscientious leader might make a call and discover the Scout’s intentions.

If, however, a Scout has been asked to leave a unit due to behavioral issues or the like, or if the council or the Boy Scouts of America has directed—for whatever reason—that the Scout must not participate, then according to the second test the Scout is not considered “active.”

In considering the third test, it is appropriate for units to set reasonable expectations for attendance and participation. Then it is simple: Those who meet them are “active.” But those who do not must be given the opportunity to qualify under the third-test alternative above. To do so, they must first offer an acceptable explanation. Certainly, there are medical, educational, family, and other issues that for practical purposes prevent higher levels of participation. These must be considered. Would the Scout have been more active if he or she could have? If so, for purposes of advancement, the Scout is deemed “active.”

We must also recognize the many worthwhile opportunities beyond Scouting. Taking advantage of these opportunities and participating in them may be used to explain why unit participation falls short. Examples might include involvement in religious activities, school, sports, or clubs that also develop character,

citizenship, leadership, or mental and physical fitness. The additional learning and growth experiences these provide can reinforce the lessons of Scouting and also give young people the opportunity to put them into practice in a different setting.

It is reasonable to accept that competition for a Scout’s time will become intense, especially as the Scout grows older and wants to take advantage of positive “outside” opportunities. This can make full-time dedication to the unit difficult to balance. A fair leader, therefore, will seek ways to empower the Scout to plan personal growth opportunities both inside and outside Scouting, and consider them part of the overall positive life experience for which the Boy Scouts of America is a driving force.

A board of review can accept an explanation if it can be reasonably sure there have been sufficient influences in the Scout’s life that the Scout is meeting our aims. The board members must satisfy themselves that the Scout is the sort of person who, based on present behavior, will contribute to the Boy Scouts of America’s mission. Consequently, the board can grant the rank regardless of the Scout’s current or most recent level of activity in Scouting. Note that it may be more difficult, though not impossible, for a younger member to pass through the third-test alternative than for one more experienced in our lessons.

4.2.3.2 Demonstrate Scout Spirit

The ideals of the Boy Scouts of America are spelled out in the Scout Oath, Scout Law, Scout motto, and Scout slogan. Members incorporating these ideals into their daily lives at home, at school, in their religious life, and in their neighborhoods, for example, are said to have Scout spirit. In evaluating whether this requirement has been fulfilled, it may be best to begin by asking the Scout to explain what Scout spirit, living the Scout Oath and Scout Law, and duty to God means to them. Young people know when they are being kind or helpful, or a good friend to others. They know when they are cheerful, or trustworthy, or reverent. All of us, young and old, know how we act when no one else is around.

“Scout spirit” refers to ideals and values; it is not the same as “school spirit.”

A leader typically asks for examples of how a Scout has lived the Oath and Law. It might also be useful to invite examples of when the Scout did not. This is not something to push, but it can help with the realization that sometimes we fail to live by our ideals, and that we all can do better. This also sends a message that a Scout can admit mistakes, yet still advance. Or in a serious situation—such as alcohol or illegal drug use—understand why advancement might not be appropriate just now. This is a sensitive issue and must be treated carefully. Most Scout leaders do their best to live by the Oath and Law, but any one of them may look back on years past and wish that, at times, they had acted differently. We learn from these experiences and improve and grow. We can look for the same in our youth.

Evaluating Scout spirit will always be a judgment call, but through getting to know a Scout and by asking probing questions, we can get a feel for it. We can say, however, that we do not measure Scout spirit by counting meetings and outings attended. It is indicated, instead, by the way the Scout lives daily life.

4.2.3.3 Service Projects

Basic to the lessons in Scouting, especially regarding citizenship, service projects are a key element in the Journey to Excellence recognition program for councils, districts, and units. They should be a regular and critical part of the program in every pack, troop, crew, and ship.

Service projects required for ranks other than Eagle must be approved according to what is written in the requirements and may be conducted individually or through participation in patrol or troop efforts. They also may be approved for those assisting on Eagle Scout service projects. Service project work for ranks other than Eagle clearly calls for participation only. Planning, development, or leadership must not be required.

Time that Scouts spend assisting on Eagle service projects should be allowed in meeting these requirements. Note that Eagle projects do not have a minimum time requirement, but call for planning and development, and leadership of others, and must be preapproved by the council or district. (See “The Eagle Scout Service Project,” 9.0.2.0.)

The National Health and Safety Committee has issued two documents that work together to assist youth and adult leaders in planning and safely conducting service projects: Service Project Planning Guidelines, and its companion, Age Guidelines for Tool Use and Work at Elevations or Excavations. Unit leadership should be familiar with both documents.

4.2.3.4 Positions of Responsibility

“Serve actively in your unit for a period of … months in one or more … positions of responsibility” is an accomplishment every candidate for Star, Life, or Eagle must achieve. The following will help to determine whether a Scout has fulfilled the requirement.

4.2.3.4.1 Positions Must Be Chosen From Among Those Listed. The position must be listed in the position of responsibility requirement shown in the most current edition of Scouts BSA Requirements. Since more than one member may hold some positions—“instructor,” for example—it is expected that even very large units are able to provide sufficient opportunities within the list. The only exception involves Lone Scouts, who may use positions in school, in their religious organization, in a club, or elsewhere in the community. Units do not have authority to require specific positions of responsibility for a rank. For example, they must not require a Scout to be senior patrol leader to obtain the Eagle rank.

Service in positions of responsibility in provisional units, such as a jamboree troop or Philmont trek crew, do not count toward this requirement.

For Star and Life ranks only, a unit leader may assign, as a substitute for the position of responsibility, a leadership project that helps the unit. If this is done, the unit leader should consult the unit committee and unit advancement coordinator to arrive at suitable standards. The experience should provide lessons similar to those of the listed positions, but it must not be confused with, or compared to, the scope of an Eagle Scout service project. It may be productive in many cases for the Scout to propose a leadership project that is discussed with the unit leader and then “assigned.”

4.2.3.4.2 Meeting the Time Test May Involve Any Number of Positions. The requirement calls for a period of months. Any number of positions may be held as long as total service time equals at least the number of months required. Holding simultaneous positions does not shorten the required number of months. Positions need not flow from one to the other; there may be gaps between them. This applies to all qualified members including Lone Scouts.

When a Scout assumes a position of responsibility, something related to the desired results must happen.

4.2.3.4.3 Meeting Unit Expectations. If a unit has established expectations for positions of responsibility, and if, within reason (see the note under “Rank Requirements Overview,” 4.2.3.0), based on the Scout’s personal skill set, these expectations have been met, the Scout has fulfilled the requirement. When a Scout assumes a position, something related to the desired results must happen. It is a disservice to the Scout and to the unit to reward work that has not been done. Holding a position and doing nothing, producing no results, is unacceptable. Some degree of responsibility must be practiced, taken, or accepted.

Regardless of a unit’s expectations or policy, if a unit takes time off, such as during the summer months, it must count that time toward service in a position of responsibility. (See “Active Participation,” 4.2.3.1.)

4.2.3.4.4 Meeting the Requirement in the Absence of Unit Expectations. It is best when a Scout’s leaders provide position descriptions, and then direction, coaching, and support. Where this occurs and is done well, the young person will likely succeed. When this support, for whatever reason, is unavailable or otherwise not provided—or when there are no clearly established expectations—then an adult leader or the Scout, or both, should work out the responsibilities to fulfill. In doing so, neither the position’s purpose nor degree of difficulty may be altered significantly or diminished. Consult the current BSA literature published for leaders in Scouts BSA, Venturing, or Sea Scouts for guidelines on the responsibilities that might be fulfilled in the various positions of responsibility.

Under the above scenario, if it is left to the Scout to determine what should be done, and the Scout makes a reasonable effort to perform accordingly for the time specified, then the requirement is fulfilled. Even if the effort or results are not necessarily what the unit leader, members of a board of review, or others involved may want to see, the Scout must not be held to unestablished expectations.

4.2.3.4.5 When Responsibilities Are Not Met. If a unit has clearly established expectations for position(s) held, then—within reason—a Scout must meet them through the prescribed time. If a Scout is not meeting expectations, then this must be communicated early. Unit leadership may work toward a constructive result by asking the Scout what he or she thinks should have been accomplished in that time. What is the Scout’s concept of the position? What does the Scout think the troop leaders—youth and adult—expect? What has the Scout done well? What needs improvement? Often this questioning approach can lead a young person to the decision to measure up. The Scout will tell the leaders how much of the service time should be recorded and what he or she will change to better meet expectations.

If it becomes clear that the Scout’s performance will not improve, then it is acceptable to remove the Scout from the position. It is the unit leader’s responsibility to address these situations promptly. Every effort should have been made while the Scout was in the position to ensure the Scout understood expectations and was regularly supported toward reasonably acceptable performance. It is unfair and inappropriate—after six months, for example—to surprise someone who thinks his or her performance has been fine with news that the performance is now considered unsatisfactory. In this case, the Scout must be given credit for the time.

Only in rare cases—if ever—should troop leaders inform a Scout that time, once served, will not count.

If a Scout believes the duties of the position have been performed satisfactorily but the unit leader disagrees, then the possibility that expectations are unreasonable or were not clearly conveyed to the youth should be considered. If after discussions between the Scout and the unit leader— and perhaps the parents or guardians—the Scout believes the expectations are unreasonable, then upon completing the remaining requirements, the Scout must be granted a board of review. If the Scout is an Eagle candidate, then he or she may request a board of review under disputed circumstances (see “Initiating Eagle Scout Board of Review Under Disputed Circumstances,” 8.0.3.2).

4.2.3.4.6 “Responsibility” and “Leadership.” Many suggest this requirement should call for a position of “leadership” rather than simply of “responsibility.” Taking and accepting responsibility, however, is a key foundation for leadership. One cannot lead effectively without it. The requirement as written recognizes the different personalities, talents, and skill sets in all of us. Some seem destined to be “the leader of the group.” Others provide quality support and strong examples behind the scenes. Without the latter, the leaders in charge have little chance for success. Thus, the work of the supporters becomes part of the overall leadership effort.

4.2.3.5 Unit Leader (Scoutmaster) Conference

The unit leader (Scoutmaster) conference, regardless of the rank or program, is conducted according to the guidelines in the Troop Leader Guidebook (volume 1). Note that a Scout must participate or take part in one; it is not a “test.” Requirements do not say the Scout must “pass” a conference. While it makes sense to hold one after other requirements for a rank are met, it is not required that it be the last step before the board of review. This is an important consideration for Scouts on a tight schedule to meet requirements before age 18. Last-minute work can sometimes make it impossible to fit the conference in before that time. Scheduling it earlier can avoid unnecessary extension requests.

The conference is not a retest of the requirements upon which a Scout has been signed off. It is a forum for discussing topics such as ambitions, life purpose, and goals for future achievement, for counseling, and also for obtaining feedback on the unit’s program. In some cases, work left to be completed—and perhaps why it has not been completed—may be discussed just as easily as that which is finished. Ultimately, conference timing is up to the unit. Some leaders hold more than one along the way, and the Scout must be allowed to count any of them toward the requirement.

Scoutmaster conferences are meant to be face-to-face, personal experiences. They relate not only to the Scouting method of advancement, but also to that of adult association. Scoutmaster conferences should be held with a level of privacy acceptable under the BSA’s rules regarding Youth Protection. Parents or guardians and other Scouts within hearing range of the conversation may influence the Scout’s participation. For this reason, the conferences should not be held in an online setting.

While it is intended that the conference be conducted between the unit leader and the Scout, it may sometimes be necessary for the unit leader to designate an assistant unit leader to conduct the conference. For example, if the Scoutmaster is unavailable for an extended period of time or in larger troops where a Scout’s advancement would be delayed unnecessarily, then it would be appropriate for an assistant Scoutmaster (21 years old or older) to be designated to conduct the conference.

Unit leaders do not have the authority to deny a Scout a conference that is necessary to meet the requirements for the rank. Unit leaders must not require the Eagle Scout Service Project Workbook, the Eagle Scout Rank Application, statement of ambitions and life purpose, or list of positions, honors, and awards as a prerequisite to holding a unit leader conference for the Eagle Scout rank. If a unit leader conference is denied, a Scout who believes all the other requirements have been completed may still request a board of review. See “Boards of Review Must Be Granted When Requirements Are Met,” 8.0.0.2. If an Eagle Scout candidate is denied a conference, it may become grounds for a board of review under disputed circumstances. See “Initiating Eagle Scout Board of Review Under Disputed Circumstances,” 8.0.3.2.

4.2.3.6 Fulfilling More Than One Requirement With a Single Activity

From time to time it may be appropriate for a Scout to apply what was done to meet one requirement toward the completion of another. In deciding whether to allow this, unit leaders or merit badge counselors should consider the following.

When, for all practical purposes, two requirements match up exactly and have the same basic intent—for example, camping nights for Second Class and First Class ranks and for the Camping merit badge—it is appropriate and permissible, unless it is stated otherwise in the requirements, to use those matching activities for both the ranks and the merit badge.

Where matching requirements are oriented toward safety, such as those related to first aid or CPR, the person signing off the requirements should be satisfied the Scout remembers what was learned from the previous experience.

Some requirements may have the appearance of aligning, but upon further examination actually differ. These seemingly similar requirements usually have nuances intended to create quite different experiences. The Communication and Citizenship in the Community merit badges are a good example. Each requires the Scout to attend a public meeting, but that is where the similarity ends. For Communication, the Scout is asked to practice active listening skills during the meeting and present an objective report that includes all points of view. For Citizenship, the Scout is asked to examine differences in opinions and then to defend one side. The Scout may attend the same public meeting, but to pass the requirements for both merit badges the Scout must actively listen and prepare a report, and also examine differences in opinion and defend one side.

When contemplating whether to double-count service hours or a service project, and apply the same work to pass a second advancement requirement, each Scout should consider: “Do I want to get double credit for helping others this one time, or do I want to undertake a second effort and make a greater difference in the lives of even more people?” To reach a decision, each Scout should follow familiar guideposts found in some of those words and phrases we live by, such as “helpful,” “kind,” “Do a Good Turn Daily,” and “help other people at all times.”

Counting service hours for school or elsewhere in the community and also for advancement is not considered double counting since the hours are counted only once for advancement purposes.

As Scout leaders and advancement administrators, we must ask ourselves an even more pointed question: “Is it my goal to produce Scouts who check a task off a list or Scouts who will become the leaders in our communities?” To answer our own question, we should consult the same criteria that guide Scouts.